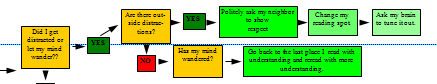

Being distracted and letting our minds wander can happen to any of us, but what can we do about it when we’re reading?

First, we need to understand that distractions are external and letting our minds wander is internal. Making a list of our common distractions and wanderings helps make us more aware of these things, which, although counter-intuitive, is just what we need. Once we’re metacognitively aware, we can do something about the problem. My students make long lists of distractions, but my personal distractions are pretty much limited to mosquitoes and fireworks (thus are the hazards of living in tropical, but festive, Ecuador). Under the category of letting your mind wander, my students generally have short lists (what happened at recess, things not going well at home), where my brain often feels like popcorn as I battle with various to-do lists, obsessive replays of the day, and thoughts about what I should be doing rather than reading.

We explain that we all have good days and bad days with distractability and wanderability; it happens to the best of readers, but good reader DO something about it. We brainstorm ideas with the kids, and if none of the following comes up in discussion, we suggest them:

- Students often need to move away from others in order to have less distractions, and we have a number of hidey-holes around the classroom for those students.

- Sometimes a student who IS a distraction needs to be asked to read in one of these spaces away from others. Sometimes we even give them names: Ricky’s Retreat and Charlie’s Corner.

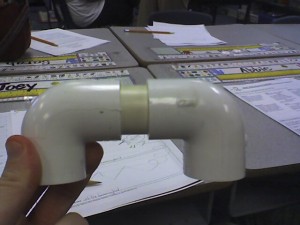

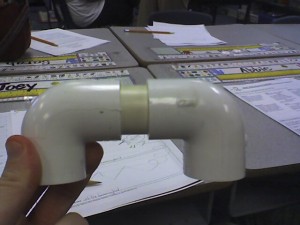

- Other students benefit from reading aloud to focus their attention. We arm them with read-out-loud phones (see photo), move them away from other students and they read away! (I have a class set of these that some parents made from PVC pipe. We use them often with both reading and writing. There’s nothing like reading your work out loud for sentence fluency!)

- When our brain is wandering with to-do lists and remembered chores, sometimes the best thing to do is stop reading for a moment and jot down what we’re thinking about and then go back to the book.

- The main strategy we use is to talk to our brains. If the distraction is something we can’t do anything about, like the leaf blower running outside our window, we simply tell our brains to pay attention. It works! At the beginning of each year we study the different controls in our brains from the website All Kinds of Minds, and students are used to thinking and speaking about these controls.

Are you more bedeviled by distractions or letting your mind wander??

Photo credit: thepeoplebrand.com/…/06/Photo_032707_001.jpg